What are lay-offs and short-time working and how can small businesses use these provisions legally and productively as alternatives to redundancy? Employment lawyer Catherine Wilson explains what these terms mean and what employers need to consider.

The recent P&O Ferries debacle and the legacy of lockdown from March 2020 have heightened the issues surrounding lay-offs and short-time working in the business environment.

Much of the employment legislation is focused on larger-scale redundancies involving 20 or more employees, which involves specific rules and regulations, as well as consultation and discussion with trade union/elected employee representatives.

Small and medium-sized employers are highly unlikely to face such large-scale situations; however, smaller-scale redundancies can occur from time to time and still require careful handling to avoid unnecessary and time-consuming disputes. Individual consultation with affected employees and a robust selection process are essential requirements of a fair process.

What does laying off mean?

The phrase “lay-off” is often used colloquially to generally describe the redundancy of staff. Lay-off also has a more specific meaning in the context of legal alternatives to redundancies (redeployment is another example of this), which can have a number of benefits for employers and employees alike. The focus of this remainder of this article is to describe these options in more detail.

The strategic use of either short-time working or lay-offs can avoid the need for redundancies and associated financial compensation, and may therefore provide the business with some much-needed breathing space.

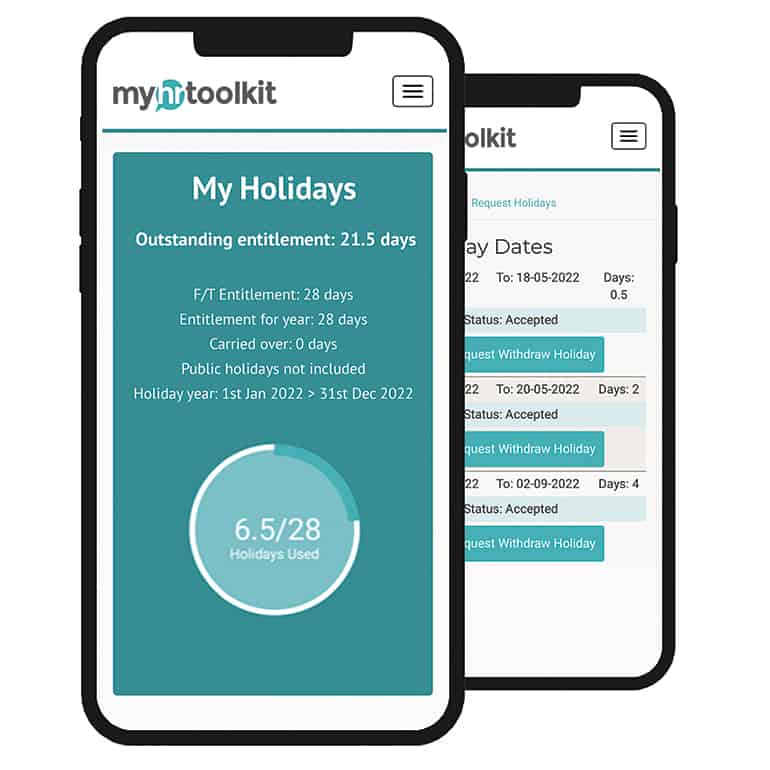

Track all types of absence across your business with an absence management software system created for SMEs.

The legal definitions

- An employee is considered to be legally laid off during a particular week if, under their contract, they get no pay of any kind from their employer for that week because there is no work for them to do, although they are available for work.

- An employee is considered to be on short-time for a week if during that week they work reduced hours and get less than half a week’s pay (section 147 Employment Rights Act 1996).

Crucially, a statutory redundancy payment may only be claimed by an employee who is working short-time or laid off if they give notice in writing to their employer. I set out the specific notice provisions for this below.

What do employers need to consider when laying off employees?

An employer can only impose short-time working or lay-offs on their employees if there is an existing term within their contract of employment. Historically viewed as a hangover from the 1970s, many modern style employment contracts had deleted any reference to the employer’s right to impose short-time working or lay-offs. The implications of COVID-19 and lockdown, however, have now encouraged many employers to consider the reintroduction of short-time or lay-off clauses in their future contracts of employment.

In the absence of any provision, the employer will have to vary the employee’s contract normally by obtaining the employee’s express consent to the change. This change could be agreed on either a temporary, or ideally, a permanent basis. The imposition of short-time working, in the absence of employee consent, leaves the employer vulnerable to Employment Tribunal claims for unlawful deduction from wages and potential claims for statutory redundancy payments. These are both best avoided for obvious reasons!

Pay for short-time working

The starting point is that employees should be paid full pay during short-time working or a lay-off, unless their contract allows for unpaid or reduced pay. Any contractual short-time or lay-off provision, therefore, should state how the employees’ pay will be calculated during any period of short-time working. This could include payment only for the hours worked or their pay could be enhanced in some other way.

Some employees are also entitled to receive a Statutory Guarantee Pay for the days they do not work. Eligibility criteria include a minimum of one month’s continuity of employment and confirmation that they are available for work and have not been laid off because of industrial action. An eligible employee must not refuse reasonable alternative work, even if the work is not specifically included in their personal employment contract.

Statutory Guarantee Pay is not available on days where the employee works for part of a day and is subject to a maximum of £31 a day for 5 days in any 3-month period, so a maximum of £150. An employer can, and generally does, provide a more generous scheme; this cannot be less than the statutory levels. If the contract of employment does not provide for less or no payment during a period of short-time working, then the employer must not do so.

How long can short-time working or lay-off last?

There is no statutory time limit on how long short-time working or lay-offs can last. A redundancy payment, however, may be claimed by a worker who has been laid off or is on short-time if they give notice in writing to their employer of their intention to claim and the claim is submitted within four weeks of either:

- The end of a continuous period of lay-off or short-time of four or more weeks’ duration; or

- The end of a period of six weeks’ lay-off or short-time working out of 13 weeks (where not more than three weeks were consecutive)

The employee must then terminate their contract by giving the greater of either their contractual notice or one week’s notice. The employer may then contest the notice by issuing a counter notice within seven days of receipt of the employee’s notice of intention to claim a statutory redundancy payment.

It is noteworthy that even if an employee fails to comply with these requirements, they may still claim that they have been constructively dismissed for redundancy if they are laid off in fundamental breach of their contract of employment. This is not straightforward and therefore advice should be sought if this situation arises.

Written by Catherine Wilson

Catherine is an expert employment lawyer and HR problem solver. She works as an Employment Partner at W Legal Limited and also runs her own employment law and HR consultancy, training, and writing business, McBrownie Ltd.

Holiday Planner

Holiday Planner Absence Management

Absence Management Performance Management

Performance Management Staff Management

Staff Management Document Management

Document Management Reporting

Reporting Health and Safety Management

Health and Safety Management Task Management

Task Management Security Centre

Security Centre Self Service

Self Service Mobile

Mobile